Sarah Meny-Gibert

— Featured on News24

[nectar_dropcap color=”#1e83ec”]R [/nectar_dropcap]eforming the way the civil service works can effect positive change for SA.

It is tempting to think that the exit of our sitting president will bring respite from the brand of corruption associated with his administration: the brazen looting of state-owned enterprises by the political elite. But it is not that simple.

Any new senior state leadership will inherit the same set of structural conditions that have allowed cynical, self-interested politics to dominate the workings of the state, and triggered the sometimes violent struggles over political and administrative office in some of the country’s provinces and municipalities.

The state has never been structurally insulated from private and political interests. To address this, South Africa needs a programme of state reform that begins to build the autonomy of the civil service. This will better protect it from factional battles and inappropriate political and business interference.

In addition, how the state administration recruits, promotes and trains its civil servants should be the subject of public scrutiny and discussion – and it should be a central component of combating corruption.

Civil servants should not be in a position where they owe allegiance to a politician or faction in a department. This does not – and, arguably, should not – preclude political deployment in the senior levels of the bureaucracy. But it should, at the very least, include protections against the appointment of middle managers based on relations of patronage. At present, the executive can legally appoint officials, from heads of departments to mid-level and rank-and-file civil servants.

An anticorruption strategy needs to address the systemic damage that corruption has had on many of the country’s public organisations. Research undertaken by the Public Affairs Research Institute shows that when corruption is endemic in a department, it can paralyse decision-making and routine departmental work as state officials focus their energy on fighting factional battles for the control of state resources – or on fighting against these interests to create space to simply do their jobs.

A typical calculation for such an official may go something like this: “Who should I take direction from: my line manager or the person in my office who has a direct line to a particular political leader and/or business interests? Given that things are unclear, I will just keep my head down and not make a decision at all.”

Does an anticorruption strategy, focused on public sector reform, ignore private sector corruption? No, a programme of state reform to better insulate the administration is not about “going after public sector corruption” per se.

It is about reducing the kind of dysfunctional organisational politics in which decision-making and routine work are paralysed in departments. And it involves developing a professional civil service that actively protects its ability to work without fear or favour in support of government policy.

Such a policy may well include fighting private sector fraud and collusion.

Government is apprehensive about the Unite Against Corruption initiative, as ordinary people express a change in the nation’s mood (Leon Sadiki)

A programme for state reform of the kind advocated here should not distract South Africa from discussing how to transform its highly unequal society – still structured largely along racial lines.

However, a state fragmented by the politics of patronage and corruption is not one steered in any coherent policy direction, let alone the direction of a more progressive and redistributive set of economic policies.

So, what kinds of reforms can South Africa look at developing – or, at the very least, debating?

International experience has shown that recruitment, promotion and training for civil servants are central to protecting them from undue influence.

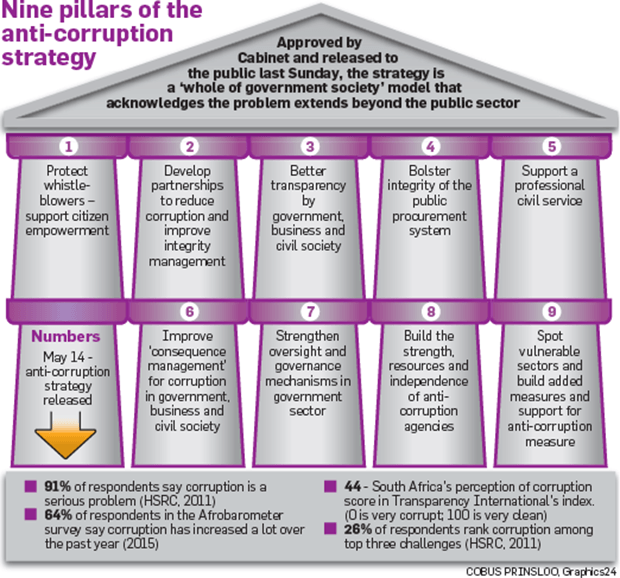

Several proposals to this effect are made in the national anti-corruption strategy document, which Minister in the Presidency Jeff Radebe released for public comment last weekend. Although there is good reason to be sceptical about the document, it contains several ideas that deserve public debate.

The discussion document calls for the phasing-in of entrance examinations for members of the senior management service – from director level up – starting with tests on relevant legislation, and then moving slowly towards standardised competency-based examinations as training institutions and courses for public servants mature.

It proposes developing a strong in-house teaching body and specialised curriculum content in the National School of Government.

The document also suggests holding a debate on the role of the Public Service Commission, which is currently mandated to monitor the administration of the public service, but lacks the legal teeth to ensure that departments and politicians comply with its findings. This could be reviewed as part of a wider debate on its role – which could include setting the exams outlined above.

Whatever the contents of the final national anti-corruption strategy, the current document and associated public consultation should stimulate a public discussion on concrete proposals for reforming state politics.

Meny-Gibert is a research fellow at the Public Affairs Research Institute and a member of the team which drafted the national anti-corruption strategy@citypress.co.za