By Emma Monama

Abstract

South Africa’s failure to transform the spatial geography of apartheid has been centrally attributed to policy failure. Drawing on empirical research in Lephalale, a town in South Africa’s Limpopo province, this article looks at the intersection between local government, spatial planning and mining companies in undoing the disintegrated apartheid geographies. It argues that understanding the failure to bridge the divided landscape requires not only a consideration of policy frameworks and issues of capacity building but, importantly, also a knowledge of the history and geography of local government institutions and the public-private interface within which policy strategies operate.

Medupi and the remaking of a new post-apartheid city

In 2006, the parastatal electricity supplier, Eskom, unveiled plans for the construction of the Medupi power station, a multi-billion-rand mega- project in Lephalale, a town located within the Lephalale Local Municipality in the Limpopo province (Phadi and Pearson 2018:vii). The project is one of South Africa’s largest investments in electricity generation, intended to solve the country’s energy crisis in the mid-2000s, culminating in the 2008 load-shedding crisis (Fig 2010:126) which have continued up to the time of writing.1 Unsurprisingly, the completion of the Medupi project ‘has been tied in the popular imagination to the end of the country’s electricity supply crisis and the resurgence of economic growth’ (Ballim 2017:11). Both the World Bank and the African Development Bank, major funders of the project, have referred to South Africa’s energy crisis as an impediment to the development of Africa’s largest and leading economy (in Sovacool and Rafey 2010). Despite an uncertain future and what others call an ‘already failed’ project (Yelland quoted in van Tilburg 2020), Medupi continues to be perceived as a viable option for electricity generation, energy security and economic development (Rafey and Sovacool 2011, Sovacool and Rafey 2010).

Besides the positive outlook, the announcement of Medupi provoked fierce debates between government institutions, industrial corporations, and civil society organisations. Opponents of the construction of the project, both nationally and internationally, argued against the US$3.78 billion loan that the parastatal received from the World Bank, concerned about the conditions under which such a loan would be granted and the project’s socio-economic and environmental impacts (Rafey and Sovacool 2011). Furthermore, Medupi’s completion date was delayed, with massive budgetary overruns, design and technical flaws (Paton 2019, Yelland 2019), and has been at the centre of corruption and fraud allegations (Fin24 March 23, 2019, Citizen December 19, 2019).

While the construction of Medupi has received attention both nationally and internationally, little has been written about the effects that this mega- project has had on the site on which it is located, the Lephalale Local Municipality. Against the backdrop of Medupi’s anticipated contribution to the country’s and the town’s economic growth, Lephalale has been classified as a ‘growth management zone’, and it is designated by the Limpopo Employment Growth and Development Plan as a ‘petrochemical cluster’. The area has also attained the status of a national development node, making it eligible for infrastructural interventions by provincial government (Limpopo Provincial Government 2010:48).

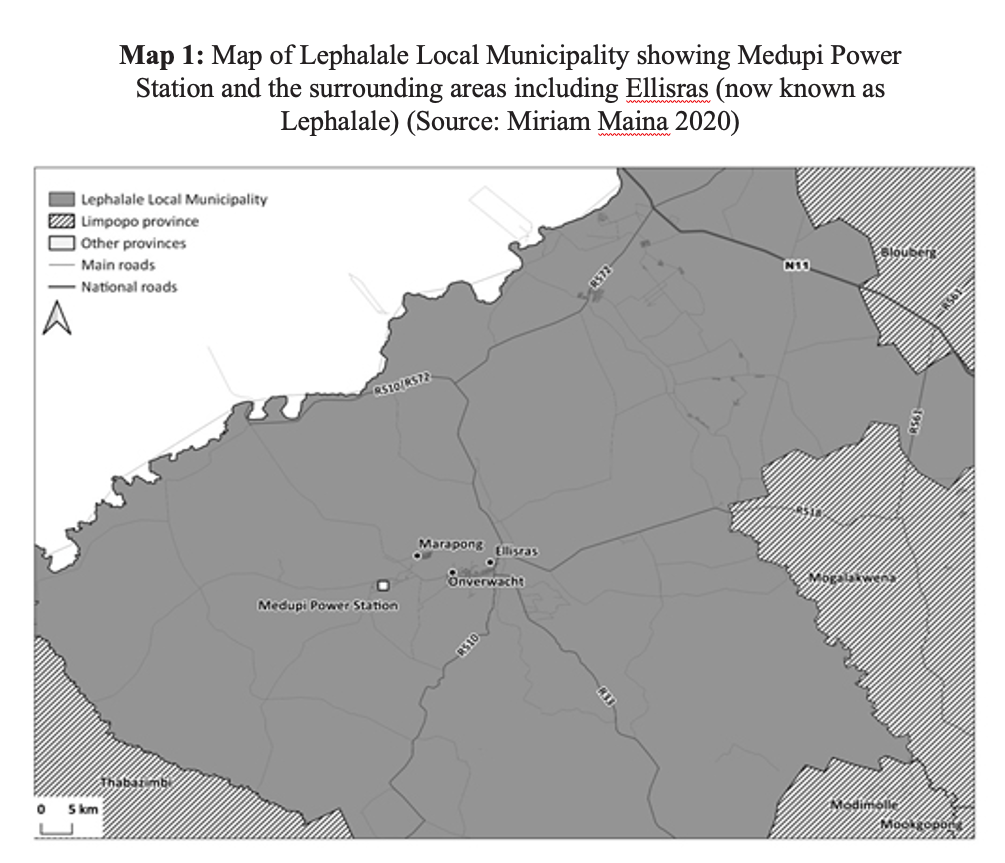

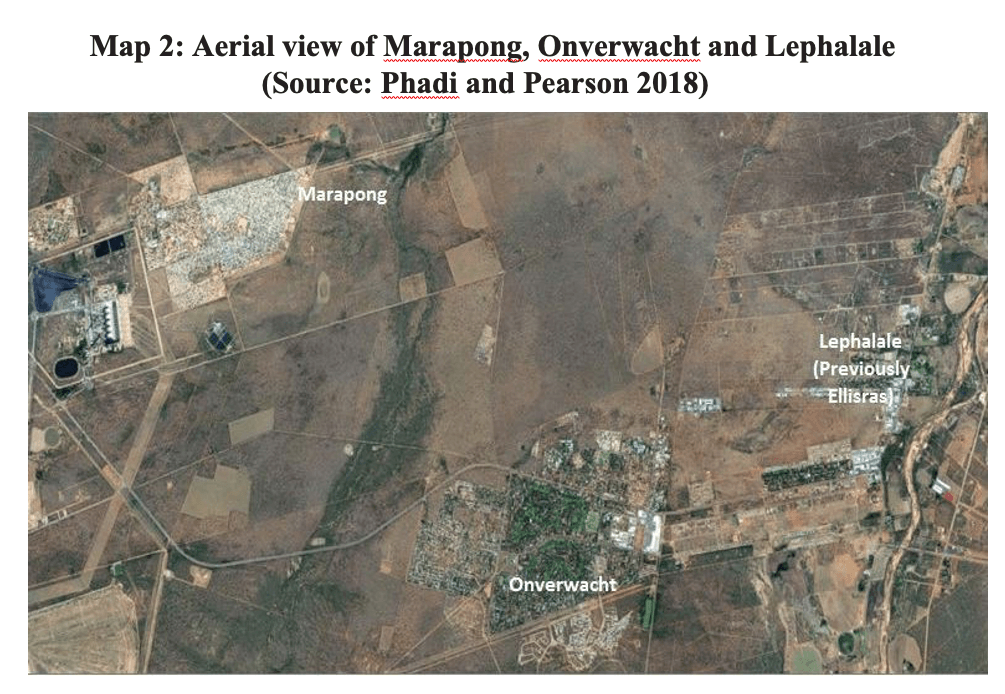

For the municipality, Medupi not only embodied the promise of economic development but held out the promise that it might become the first post-apartheid city. Following the announcement of the construction of Medupi, the municipality undertook ‘to build the first city since 1994 and to … [become] the energy hub of Africa’ (Institute for Performance Management 2013:9). In particular, the municipality saw the possibility of bringing together the splintered spatial landscape which was the legacy of apartheid planning. Apartheid’s ‘separate development’ ideology had bequeathed the region racially segregated ‘islands’ of development: two suburban areas that were previously designated ‘whites only’ (the towns of Ellisras and Onverwacht), which are located some distance from the ‘black’ township of Marapong (see map 1 and 2); further still are the villages that were once located in the Lebowa ‘homeland’.

This article argues that the Medupi project and the promise it held out has done little to bridge this divided landscape. To understand why apartheid-era spatial divides continue, this article focuses on the challenges faced by the Lephalale Local Municipality in fulfilling its stated mandate to address the legacies of spatial inequality. It seeks to explain the shifting political and economic relationships that have shaped the course of urban development in Lephalale. Drawing on 12 in-depth interviews conducted over a period of two years with former and current municipal employees, Exxaro2 representatives, and long term residents of the area, this article maps out the historical and geographical legacies of the municipality and the public-private interface within which strategies of spatial planning have been applied in three steps.

First, the article provides a historical context to the emergence of the municipality and the divided landscape in which it operates. It shows how the local government has been unable to free itself from relations of dependency established in the context of a company town. Next, the article considers how the Medupi project has exposed crippling institutional capacity shortages in the municipality, particularly over land-use planning and management, and the failure of intergovernmental cooperative governance to address this. As the then municipal manager, Edith Tukakgomo, put it, Medupi was ‘imposed’ on the small municipality (interview Tukakgomo 2015). Finally, the article considers how, in the absence of capacity within the local municipality, private interests – particularly the multinational corporation, Exxaro – stepped into the breach and re-established the Lephalale Development Forum (LDF), ostensibly to aid the municipality in the face of unprecedented development. Through this, private interests reinforced their control over the planning processes of the municipality, thus further entrenching apartheid-era spatial divisions.

Some history

Lephalale falls within the Waterberg region, an area with extensive coal deposits, and as a result, mining is the primary contributor to the district’s economy. Prior to the arrival of white settlers, the area had been occupied for centuries by Khoe-Khoe, Nguni and Sotho-Tswana speaking people (Hallowes and Munnik 2018:22). ‘White settlers only arrived in the Waterberg area in 1818; by 1850 they had started farming in the area, relying on the knowledge and resources of the people they found there’ (Zulu 2015 in Hallowes and Munnik 2018:23). From the 1850s, and especially during the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902, ‘There was a growing encroachment of white farmers onto black land in the territory claimed by the Republic of South Africa (ZAR)’ (Hallowes and Munnik 2018:26). This appropriation of land was enabled by a generous system of white entitlement (Hallowes and Munnik 2018) where white farmers and land speculators could claim farms regardless of black ownership, occupancy and use. African communities were subsequently coerced into labour tenancy, rent tenancy and share cropping (Bergh 2010 in Hallowes and Munnik 2018:26).

After the 1910 unification of South Africa, the Waterberg area was divided into farms and irrigation schemes to support ‘white agriculture’ (Tempelhoff 2018 in Hallowes and Munnik 2018:28, Tempelhoff 2017). During this time, coal deposits were discovered in the area and subsequently ‘the Waterberg was seen as an area of vast potential … a landscape to be incorporated into the mining economy of South Africa’ (Hallowes and Munnik 2018:23). In 1954, the apartheid government ‘reserved the prospecting rights of 123 farms in the Waterberg district for the sole use of the South African Coal, Oil and Gas Corporation (SASOL) and the South African Iron and Steel Corporation (ISCOR) – two of South Africa’s major parastatals’ (Ballim 2017:61). In 1957, ISCOR acquired the property rights to six farms in the area, and in the mid-1970s began developing the Grootegeluk Coal Mine (Alberts 1982) which is located about 20 kilometres from the centre of Lephalale.

While many farmers and local property owners resisted the intrusion of the company into local affairs (interview, Meyer 2015 in Ballim 2017:80), the company was gradually drawn into a program of coordinated urban planning (Ballim 2017:64). Indeed, it was through ‘ISCOR’s financial muscle…[that]… Ellisras could fulfil infrastructural requirements to afford the town municipal recognition’ (Ballim 2017:68). In 1960 the area was declared a ‘township’3 (Ballim 2017), and this meant that the area could be planned according to the town planning schemes consistent with the ideologies of the apartheid state, and its fundamental objective of racial segregation.

According to Ballim (2017:77), in 1965, the Ellisras District Development Association, a local government body comprising members of the state and residents – made up of whites only – came into being. As its name suggests, this was a development initiative with the aim of creating autonomy at the local level (Ballim 2017). This hoped-for autonomy was, however, constrained by bureaucratic procedures, most of which were linked to the emerging apartheid system. With scant resources, Ellisras looked to ISCOR to provide the necessary financial, technical and infrastructural support for urban development (Ballim 2017:67). The routine management of urban affairs in Ellisras later fell under the Peri- Urban Areas Board, a provincial governance authority with the responsibility of administering small towns. Its mandate was not to fully delegate urban governance to local authorities but to facilitate loose government oversight (Ballim 2017:77). In accordance with the then- extensive use of the Peri-Urban Areas Health Board Ordinance of 1943 (Hui and Wescoat 2019: 256), the Board could provide basic services and town planning and execute necessary public health services.4 In more densely populated areas, local area committees (for areas such as health) were elected by residents – only whites participated – to assist the board in its governing functions (Carruthers 1981:16).

Whilst the development of Ellisras was underway, black families residing in informal settlements on white owned farms were forcibly removed to the Lebowa homeland. On July 29, 1979, it was reported that all Africans were to be forcibly relocated out of designated white urban areas into the homelands in an effort to ‘bolster the viability of formally established black local authorities’ (Sunday Express 1979, cited in Ballim 2017:82). To ensure a steady supply of cheap mining labour, ISCOR built single male hostels for their employees – 20 kilometres out of Ellisras and close to Grootegeluk coal mine (Ballim 2017).

Despite being under the jurisdiction of the board and with a locally elected peri-urban health committee, ISCOR’s executive effectively performed the functions of a local municipality, said former manager, Town Planning Division, Dries de Ridder (interview, de Ridder 2015). In 1981, the state’s electricity generator – then ESCOM/EVKOM5 – acquired land from ISCOR and began work on the construction of a power station called Matimba. The resulting growth in population necessitated further upgrading of the town and its infrastructure (Buermann 1982, Phadi and Pearson 2018). ISCOR, in turn, bought vast tracts of land including a farm north of Ellisras (Ballim 2017, Phadi and Pearson 2018) on which a suburb called Onverwacht would be built along with a business centre and a recreational hub.6 The latter was intended to serve all the white staff and community around it (Ballim 2017:60).

This suburb, which was viewed as ‘an ISCOR town and a modern development’ (interview, de Ridder 2015), was located five kilometres from Ellisras’s central business district. The effect was to split local commercial activities into two separate (and increasingly antagonistic) business centres. This fragmentation, Ballim argues, was due to antagonism between ISCOR and local landowners. Long-established residents expressed both discontent and their distaste for ISCOR’s intrusive presence and for the proposed developments – and they rejected ‘the idea of a shared regional prosperity’ (Ballim 2017:82). While there were hopes that these two centres would eventually merge into a single unit, at the time of writing, that outcome is still to be realised (Ballim 2017:81).

Ellisras and its surroundings were later granted full municipal status in 1986 (Ballim 2017:77) and at the insistence of the National Party (NP), a municipal council (stadsraad) was elected to coordinate the development of the town (Phadi and Pearson 2018). This development ignited further tension, with ISCOR opposing a decision that the council members should be elected on political party platforms, arguing that this would tamper with their own administrative forms. According to Tienie Loots, the former head of the electrical department of the municipality, this created both confusion and conflict:

I was appointed as chief and I said from today, we do things like that and they [ISCOR] would tell me straight to my face who the hell are you? We have been running it like this and now you want to tell us that we must do this and that, and I said you are right, we will do it my way now because it’s now a council, we are under another law, we have laws and bylaws, and rules and regulations which are under government, not ISCOR laws. (Interview, Loots 2016)

The issue was partially resolved when several officials from ISCOR were appointed as councillors in the new municipal structure. This ensured that, despite its shifting presence in the municipality, the company continued to provide basic services and infrastructure development in the town, with specific roles reserved especially for mining officials (interview, de Ridder 2015).

By the late 1980s, as the apartheid government was under siege, and with an increasing demand for a stable workforce, ISCOR and ESCOM funded the development of a black township within the vicinity of Ellisras (Ballim 2017:113-5). Despite objections from the then-dominant Conservative Party (CP),7 and the determination of white residents of Ellisras to preserve strict racial segregation, the township of Marapong was built in 1991 (Ballim 2017, Hallowes and Munnik 2018). In line with apartheid segregationist legislation, the township was built on land which lay some distance from the white suburbs of Ellisras. Marapong was granted minimal infrastructure and to date has only one access route. From a governance perspective, prior to 1994, the township remained outside the jurisdiction of the municipality and under the administration of ESCOM, receiving its basic services only from the latter (Phadi and Pearson 2018:4).

From the mid-1980s onwards, the apartheid government’s thinking around ISCOR began to change: increasingly influenced by market-based thinking, its shares were listed on the stock-exchange. The state-owned Industrial Development Corporation retained some shares (Greenberg 2006:41) but the growing influence of the market would change the ownership face of steel production world-wide: South Africa and even social relations around governance in Lephalale would be touched by this development. By 2004, ISCOR was merged into Mittal Steel to become part of the world’s largest and most profitable metals company (Greenberg 2006:41); in 2006, it was unbundled into Kumba Resources, which retains iron ore deposits, and Exxaro, which took over the coal deposits (Clark 2014:108). In the latter move, the company became responsible for mining operations in Lephalale. While the impact of the privatisation of companies like ISCOR and SASOL on South Africa’s industrial development has been written about (Clark 2014, Roberts and Rustomjee 2009, Greenberg 2006), how these changes impacted on localities like Lephalale remains a research gap.

Following the municipal elections in 1995, and in the face of resistance and hostility from white officials to the incoming ANC government, an Ellisras-Marapong Transitional Council was established in terms of the interim Constitution. The Council would administer the affairs of a population which now included both the formerly white towns and the township of Marapong (Phadi and Pearson 2018). This, as one former senior official put it, was ‘the end of lily-white Ellisras’ (interview, de Ridder 2015). In 2000, the Lephalale Local Municipality was formally constituted, comprising Ellisras, Onverwacht, Marapong and thirty-eight surrounding villages under a single municipal structure. This changed the composition both of the electorate and council (Phadi and Pearson 2018:6) and brought with it increased demands for service delivery.

The foregoing demonstrates how ISCOR was important and central to the spatial development of Lephalale (previously Ellisras) and its surrounding areas. The governance of the town, while subject to national government policies, was the result of the interface between ISCOR, state officials, locally elected governing structures and later, ESCOM. Whilst the case of Lephalale exemplifies those of mining towns whose governance has thus far been transferred to democratically elected institutions (Mocwagae and Cloete 2019), the new governing structures have failed to shift historically constituted power dynamics. While its immediate role in administration and planning diminished post-1994, ISCOR (now called Exxaro) and ESCOM (now Eskom) continue to have direct control over various services in the area, including the purification and provision of water. These, along with the issue of land ownership, are fleshed out later in the article in order to highlight how the municipality remains heavily dependent on both companies for service delivery, undermining its desire for self-sufficiency in building the new city.

While the effects of the privatisation of ISCOR were not discussed in interviews, it can be shown that the company continues to do as it pleases even in the post-apartheid era. Exxaro insists on being involved in every planning phase of the municipality by claiming that they are an important role player, if not a leader, in the developments that have taken place in the area. Recognising their continued role and influence over the town’s developments, Johan Wepener, the manager of Grootegeluk mine, states:

Since 1994, people in the municipality … know that they are still dependent on people that have run this place for a very long time. As business … we’ve done fairly well in managing the transition. (Interview, Wepener 2015)

This is echoed by de Ridder, who argued that the management style of the company did not change with privatisation and that Exxaro is ‘still doing what they were doing 50 years ago’ (interview, de Ridder 2015).

Phadi and Pearson pose the paradox raised by this particular private- public interface: how does a municipality with no ownership to land govern its affairs? (Phadi and Pearson 2018:39). In part, this article is interested in exploring the complexities that relate to conditions of capacity, of corruption, of resources, of policy, of power, of leadership and of legitimacy and how these challenge any simplistic and one- dimensional narratives which purport to understand local government and its institutions in South Africa today. The next section, therefore, highlights how Medupi’s construction vividly exposed the municipality’s lack of institutional capacity to address integrated spatial development.

Spatial integration and the Medupi project

As mentioned, the announcement of the Medupi project spurred an interest in the construction of a new post-apartheid city which, hopefully, would address the splintered apartheid spatial planning. Lephalale’s imagined city and its guiding principles echo the visions of the Breaking New Ground strategy and the National Development Plan’s goal of integrated sustainable settlements.8 Through its own integrated urban development plan, the municipality sought – and still seeks – to reverse and close the spatial gaps between Ellisras, Marapong and Onverwacht – and, indeed, to integrate them. However, a lack of institutional capacity and the question of land ownership challenged the realisation of the conceived city and became impediments in the municipality’s quest for self-sufficiency.

The announcement of the Medupi project increased land-use applications, especially ‘between 2007 and 2010/2011’ in the municipality, according to the manager, Land Use and Spatial Planning Division, Catchlife Mutshavi (interview, Mutshavi 2015). These originated from mining and construction companies and from the local business community who wanted a stake in the town’s increasing prosperity. Both Ellisras and Onverwacht were targets of interest in infrastructural development with the latter place receiving a significant number of applications including one for the building of a shopping mall. Private developers were also keen to invest, with private accommodation becoming a much sought-after business opportunity. According to Nakkie Martins, manager of Administration and Support in the municipality, ‘Exxaro, Eskom and … everybody else – even private owners – that had stands open, land and even those who has built [had] … a lot of subdivision and rezoning … and … it was too much [work] … for … the number of people we had in town planning’ (Interview, Martins 2016). Exxaro offered to assist the municipality by appointing and paying a building inspector to ‘assist with the approval of the building plans and inspections … so that the standard of the building and the new development [was] still on track’ (interview, Martins 2016). According to Martins, the pressure to swiftly approve building plans led to ‘lots of allegations … that people were bribed’ – some of which were proved to be true (interview, Martins 2016).

Consequently, given the ‘huge pressure in the building control section’ (interview, Martins 2016), the lack of capacity in the planning division and the fast-growing demand for private accommodation in the town, there was a breakdown in compliance with municipal regulations. Following long delays and ‘facing operational deadlines’ (Kirshner and Power 2015:76), developers went ahead with their building plans undeterred by the penalties that they faced (Phadi and Pearson 2018). This obviously resulted in a collapse in building standards and, according to the manager of Buildings Control in the municipality, ‘…a lot of illegal buildings [were] constructed’, according to the manager Building Controls Division (interview, Mabale 2015). In 2012, the municipality’s Council9 established the Mayoral Planning Committee10 in order to halt unchecked developments. However, the Committee’s attempts were not successful and many sites remain unchecked for quality assurance due to the high number of applications (Phadi and Pearson 2018:16). Faced with this, the committee was terminated with the introduction of Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA) (Phadi and Pearson 2018:16).

Due to the municipality’s lack of capacity to adhere to SPLUMA’s new regulations, a two-year interim transitional plan was implemented in preparation for the establishment of a district tribunal (interview, Tukakgomo 2015). SPLUMA regulations, however, were not enough to exert pressure on companies and private developers, who, through rezoning, challenged some of the municipality’s provisions. As part of the effort to increase the capacity of the municipality, from 2009/10 until the end of the 2011/12 financial year, Exxaro offered the service of two town planners to help fast track the planning application review process in the municipality (interview, Mutshavi 2015). Whilst some regarded this intervention as beneficial to the planning division (interview, Mutshavi 2015), others had opposing views. De Ridder lamented that ‘… they [the Exxaro town planners] created a mess … [they showed] … neither performance nor dedication … and [they] didn’t contribute much’ (interview, de Ridder 2015).

Former municipality employees have also benefitted from the developments at Medupi. Familiar with the bureaucratic red tape and planning procedures of the municipality, some worked as consultants for private developers. Using their municipality networks, they assisted developers in processing their planning applications and securing approvals. The then municipal manager blames the ‘patchy’ development of the town on the failure of previous town planners, ‘…those were the mistakes done by the previous planners… He was heading the planning by then’ (interview, Tukakgomo 2015). To rectify some of these mistakes, the municipality is trying to encourage developers to provide infill development;11 however, due to a lack of land use rights, the municipality cannot develop (interview, Tukakgomo 2015).

The municipality is acutely aware of the limitations imposed on their strategic vision to develop the first post-apartheid city by their lack of land: indeed, every department interviewed by our researchers reflected on how this is one of the biggest challenges it faced. After private individuals, Exxaro owns the second highest percentage of land in the area. According the municipality’s Integrated Development Plan, ‘(w)ithin the urban edge the municipality does not own land with only 9.21 per cent belonging to government, Eskom 13.63 per cent, Exxaro 20.76 per cent and the majority which represents 56.38 per cent currently belongs to private individuals’ (Lephalale Local Municipality 2019:57). Without land, the municipality has found itself in a weak position where it is dependent on both companies and private developers in planning its imagined city. As the former mayor, Steve Ratlou, expressed:

If you come look for land you might find that one of the pieces of land you’re buying either belonged to the central government then or either ISCOR or ESCOM, period! So, the housing schemes that you see largely have been developed by those specific companies. Government was not even involved in building houses for the people. (Interview, Ratlou 2015)

According to de Ridder, farmers and private land owners have been refusing to sell their land to the municipality, making it difficult to develop integrated settlements and to close the patches between the different parts of the town (interview, de Ridder 2015). While the municipality is aware that it can expropriate land, the then municipal manager argued that they cannot expropriate land if they have not yet developed Altoostyd – a farm purchased by provincial government for low cost housing in Lephalale (interview, Tukakgomo 2015). Although the land was purchased, the infrastructural articulation process was yet to start by the time of the research. The incapacity to develop the 500 hectares of Altoostyd, according to Tukakgomo, made it even more difficult to ask for more land. For instance, Exxaro used the very same logic to refuse to give land to the municipality in order to build housing in Marapong.

Furthermore, the construction of the Medupi power station fuelled a steep rise in property prices, making it difficult for local households to keep up with the municipality’s rates and taxes. When Medupi arrived, both Eskom and Exxaro provided houses to their employees. However, according to Martins, Eskom inflated the prices of the houses they owned, while Exxaro ‘had land, empty stands and sub-divided their properties … and with the expansion of the mine, offered people stands for affordable prices … they looked after their people’ (interview, Martins 2016). For those contractors without access to land and housing, it was difficult to afford the expensive market price for housing. Martins blames Eskom for this situation, arguing that because Eskom knew about Medupi, they sought and purchased houses at inflated prices, offering them to their employees at above-market prices (interview, Martins 2016). Due to high population influx and housing demands, there was a growth of informal settlements in the vicinity of the neighbouring township of Marapong. In response, and to help manage the squatters and influx of people, Exxaro offered to lease to the municipality the site where the informal settlement was located and to provide bulk and temporary infrastructure. The company logic was that, following the completion of Medupi, people would leave the area and, when this happened, the land would still be in the hands of the company.

According to Nakkie Martins (interview, 2016), there was a lot of pressure from provincial government on the municipality to develop Altoostyd. The government wanted the land to be transferred to the municipality and for the municipality to develop it. However, the municipality decided that this would be a very expensive project as the area needs to be developed from the ground up (interview, Martins 2016). For the municipality to get money, they must, according to Martins, increase the service tariffs, but they could not do this for two reasons. First, municipal services must still be affordable, and if they are not, there would be non-payment and illegal connections. Secondly, the municipality was not responsible for some of these services. For example, Exxaro did the water purification and provision, and as Martins mentions, the municipality purchased water from Exxaro, ‘which is in fact not supposed to be but it’s how it has worked over the years’ (interview, Martins 2016). Eskom provided electricity directly to most of the communities within the Lephalale Local Municipality including Marapong township and the surrounding villages. Consequently, the province took over the Altoostyd project and has installed bulk services. Once the internal reticulation is done, the township will be transferred to the municipality, who will be responsible for the water, roads and sanitation systems (interview, Martins 2016).

A parallel administration

The process of increasing the capacity of the municipality was facilitated through the Lephalale Development Forum (LDF). This was a consultative forum established in July 2008 to ‘bring together public and private sectors to review the impact of Medupi power station in the Lephalale area’ (Veti 2014:7). One of its aims was to leverage resources and skills in order to build capacity in the local administration over the long term (Phadi and Pearson 2018:36). The forum comprised five working groups, namely, local economic development, infrastructure, social services, labour and skills, and environmental sustainability.12 In essence, the LDF was a collaborative space through which IDP strategies are aligned with the agendas of the private sector. The forum coordinated and implemented projects ranging from major infrastructural developments to socio- economic interventions. According to the Local Economic Development (LED) manager, Charity Radikwabe, through the forum, Exxaro and Eskom aligned their social labour plans and corporate citizenship agendas with the Integrated Development Plan and LED strategies of the municipality (interview, Radikwabe 2015). Following the quarterly meetings in the municipality, the different clusters meet with other LDF stakeholders to report back to them (interview, Martins 2016).

The LDF assumed a significant role in the recent development of Lephalale: according to a local pharmacist, Ferdi Steyn, it is not new (interview, Steyn 2015). The structure has informally existed since the transition to municipal administration but was re-established to facilitate various projects in the wake of the construction of Medupi. Exxaro and Eskom have funded the LDF for at least the last three years.13 This funding created tension over the structure’s legitimacy, with the manager of Grootegeluk mine (which belongs to the Exxaro group), Johan Wepener, arguing that it is ‘a non-governmental structure’ (interview, Wepener 2015) and Tukakgomo, the then municipal manager, arguing that, from its inception, the LDF was ‘a government initiative’ (interview, Tukakgomo 2015). According to Martins, the LDF was started by John Erasmus, a previous town clerk who was acting as municipal manager, but at the time the structure was not as effective as it later became. The LDF was established to avoid the ‘political interferences’ and, as such, no councillors should be part of it. This decision to close it to their membership, she continued, presented a ‘big problem’ for councillors and for the mayor (interview, Martins 2016). Accordingly, Phadi and Pearson (2018) have argued that the LDF constitutes a parallel structure to a municipal administration, raising questions about who runs the municipality. Using Gaventa’s power cube framework (2006), the paper analyses the power struggle that emerged between the LDF and the municipality by considering the spaces, levels and forms of power and their interrelationship in the process of decision-making.

Whilst the LDF is recognised as a platform for engagement and discussion, the question of whether this represents a shift in decision- making power remains to be answered (Houghton 2011, Sinwell 2010, Gaventa 2006). For instance, while the LDF structure was heralded as ‘the driver of solving problems’, said Rudzani Ngobeli, manager Public Works Division (interview, Ngobeli 2015), others see it as nothing more than a decision-making and assurance scheme run by the mining and energy companies – indeed, it was even called ‘an agent of self-interest’ (interview, Wepener 2015). According to Tukakgomo, the ‘LDF was formed with good intentions but [those] who were leading it manipulated its systems and privatized it… and [the] LDF was then seen as a private initiative run by Exxaro which was not supposed to be the case’ (interview, Tukakgomo 2015).

Despite the contestations over the structure’s authority and intentions, for both the municipality and Exxaro, the LDF has proved able to navigate

– even, perhaps, to bypass – bureaucratic red tape. According to the then executive manager of strategic management, Kgoroshi Motebele, the LDF is ‘a very efficient way in which things work out … [it made] … a huge impact … [and] … contribution’. Therefore, he continued, the LDF should not be seen as a ‘foreign or extra organization with its own [agenda]’ (interview, Motebele 2015). It is thus unsurprising that the relationship between the municipality, Exxaro and Eskom is perceived as a beneficial one, with the latter two offering support to the municipality (interview, de Ridder 2015). Through the LDF, Exxaro has contributed to various infrastructural projects including constructing schools, building new roads and upgrading old ones, and establishing health facilities.

While the benefits of the LDF seem obvious, it is necessary to consider the power relations between the respective parties and the environment (Miraftab 2004) under which the forum re-emerged and the role it assumed. Although the establishment of the LDF marked the ‘inclusion of a broad range of actors’ (Burki et al 1999 in Miraftab 2004:4) into the processes of the municipality, the discourse of inclusion and collaboration concealed the boundaries of authority and power in the decision-making processes. Both Exxaro and Eskom played a dominant role in the development projects that have sprung up with the construction of Medupi. According to Mocwagae and Cloete (2019:78), this complicates the implementation of the municipality’s other plans, such as the Spatial Development Framework. The LDF re-emerged in the context where the mining boom and associated ‘flow of labour’ and capital ‘occurred largely in the context of limited capacity, inconsistent planning measures and infrastructures’ (Kirshner and Power 2015:76). The municipality was ‘ill- prepared to manage the multiple pressures and cumulative effects arising from the coal operations’ (Kirshner and Power 2015:76) and the weak intergovernmental cooperation in institutional capacity for planning and administering urban development (Kirshner and Power 2015). Given this, Exxaro’s infrastructural power and technical expertise supplement the municipality’s ‘lack’ of capacity (Butcher 2018), thus assuming a pivotal role in leading the growth of the town of Lephalale.

Lephalale’s current fragmented spatial organisation cannot be understood outside the apartheid legacies which are embedded in the current manifestation of contradictions – the lack of land being the main problem. The town’s ‘patchy’ geography is shaped by, and in turn reflects, the economic, political and spatial histories of the apartheid years as well as ‘the long-history of governance through concessions’ between the state and mining interests (Kirshner and Power 2015:72). Subsequently, understanding the current state of urban development in the area requires an analysis of the historical and contemporary interface between local government and mining companies. Given the role of mining in the country’s urban development history, understanding territorial imaginations and practices require a ‘pluralist’ approach to the ‘spatial arrangements … [by] … which power is deployed and experienced which is not limited to the state’ (Agnew 2013:1-2). While mining companies have never achieved complete autonomy (Ballim 2017, Butcher 2018), their ‘territorial power … built over decades of negotiating sovereignty over land … [is] one [which] the state has been both complicit in and contested’ (Butcher 2018:2188). This has given the mining industry in South Africa unparalleled power in the negotiation of contemporary urban spatial developments and trajectories of local economic development.

Through its access to funding, the LDF has been positioned as an independent structure whose role has been defined as just a supporting arm of the municipality. As a non–governmental structure, the LDF therefore does not need to adhere to nor go through all the bureaucratic procedures, municipal by-laws and approval processes which are required from local government. According Wepener, the municipality wanted to take over the structure and turn it into a Lephalale development agency; however, Exxaro threatened to withdraw. While the company agrees on priorities jointly with the municipality, helping the municipality to lodge for funding at provincial, and national level, it oversees the construction and project phase of implementation (interview, Wepener 2015). Through this modus operandi, Exxaro has continued to contribute infrastructure, human resources and land ‘selectively and strategically’ (Kirshner and Power 2015:27), choosing how – and, indeed, when – to assist.

The independence and resulting immunity of the LDF from institutional accountability has been criticised as self-serving and also for isolating the municipality from access to information and key decisions (Phadi and Pearson 2018). Despite their lack of formal responsibility, Exxaro can access information on all local projects and from all the relevant municipal departments. Radikwabe, the LED manager in the municipality, claims that the LDF secretary, appointed by MAC Group on behalf of Exxaro,14 concealed information from the municipality in order to further corporate interests. The secretary is alleged to have pointed to the municipality as ‘not interested’ in the Lephalale Development Forum, with officials arguing that he was actively ‘refusing to engage them, to involve them’ (interview, Tukakgomo 2015). According to the then municipal manager, Tukakgomo, since joining the municipality in 2012, Radikwabe has been ‘struggling to penetrate to the LDF, struggling to penetrate to [the secretariat] …, and you can’t say people were not there, people were not interested’ (interview, Tukakgomo 2015). The Forum thus facilitates the company’s access to information – a valuable resource – regarding stakeholder participation in the development of the town. As Radikwabe argues: ‘He is coordinating … he is facilitating things, he has information … as an LED manager you don’t have that much information … remember, information is power’ (interview, Radikwabe 2015).

Although Exxaro sees itself as part of the broader community of Lephalale, dedicated to its social and economic growth, the LDF’s constitution, ‘definitional ambiguity’ (Miraftab 2004:92) and processes reveals little to suggest a commitment towards democratic processes and goals. The LDF’s independence and resultant selective and strategic development has resulted in a form of extractive urbanism reinforcing segregated spatial patterns. Infrastructural developments, including transport systems and residential patterns ‘emphasize the hyper-mobility of resource commodities … for extracting raw materials for export and creating links with the country’s industrializing [and industrialized] economies’ (Bridge 2009 in Kirshner and Power 2015:73). By posing as patrons and sponsors of the development of the town and community at large, Exxaro has gained a certain legitimacy (Keating 2014:1), even when its motives are obscure. As such, despite the ‘contentious and ambiguous’ (Bebbington et al 2008:887) relationship between mining and development, many do believe that the expansion of mining in the area could lead to sustained ‘economic development’ of the town. Despite a bleak future for an integrated urban future, others believe ‘… that transformation and the growth [of a city] … will come eventually’ (interview, Cilliers [manager communications division] 2015; interview, Wepener 2015). Whilst it is difficult to measure the LDF’s success and effectiveness as a space to facilitate local economic development, its power to share expertise and provide funding for the municipality (Houghton 2011) is recognised. There are, however, very few concrete proposals to suggest how economic, structural and spatial transformation is to be achieved and there is ‘little evidence that the extractive industry is effecting any such transformation’ (Kirshner and Power 2015:76).

Conclusion

This article sought to understand how, in the current environment, mining companies have, through new governing structures, policy mandates and their historically constituted infrastructural power and technical expertise, continued to have access to administrative structures and influence over local development. Using spatial planning as an entry point to questions of who governs in a local municipality, the case of Lephalale Local Municipality broadens understandings of how mining towns are governed through asymmetrical concessions between public and private interests. Specifically, the idea of capacity provision was instrumentalised by Exxaro and Eskom in ways that ensured them access to municipal processes and projects, but they did little to address the spatial disparities at the core of the municipality’s developmental dilemma. Instead, both companies, along with private developers and landowners, prioritised their own agendas, perpetuating the exploitative and extractive urbanism characteristic of Lephalale’s patchy geography. This article demonstrates how the town’s spatial planning continues to be shaped by the state, mining companies, private developers and land owners, and how power is constantly shifting between multiple interests.

The point is that the municipality, because of a history of colonial and apartheid dispossession, finds itself at the mercy of powerful public- turned-private companies who own the land and are in control of various other resources in the town. The article shows how the solutions to issues many municipalities face move beyond simplistic and one-dimensional aspects of corruption, capacity, skills, policy, leadership or resources toward a more complex understanding of how these intersect to produce local histories, geographies and specificities. At their core, often, they require a rethinking of historically constituted bureaucratic structures and modalities of governance which are embedded in histories of dispossession. Addressing spatial inequalities in South Africa is not only a matter of policy direction and capacity at the local level; intertwined with these is the question of land without which any attempt at undoing apartheid geographies becomes nothing more than radical rhetoric with conservative practices (Kepe and Hall 2018). The article extends earlier work, and emphasizes the need for further research, on the histories of rural-urban land conversion and the shifting economic and political relationships (Mabin 1993) shaping urban development in apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa. More generally, the findings raise the question as to whether the most determining factor in Lephalale is not the influence of mining interests per se, but rather the nature of the capitalist economy.

Notes

- ‘Load shedding’ is the popular and official term used to define electricity blackouts in South Africa.

- A multinational coal-mining company which operates in the area, descended from the state-owned ISCOR.

- The term ‘township’, in postcolonial Africa particularly, has a double In planning terms, it is used to denote ‘land allocated to host the site of a town and refers to both residential and industrial sites’ (Bond 2008:406). The term is also most commonly – in South Africa – used to denote black urban settlements constructed during the time of apartheid.

- ‘Peri-urban areas are widely considered as amorphous undisciplined places fraught with congestion, pollution, water and sanitation problems’ (Allen et al 2016 in Hui and Wescoat 2019:2). Such spaces are characterised by ‘diverse and changing geographic connotations’. The concept dates back to the 1930s and ‘has become [a] widely used term worldwide for settlement beyond the boundary of a city’ (Woltjer et al 2014 in Hui and Wescoat 2019:2).

- Eskom was previously ESCOM – the Electricity Supply COMmission – also called EVKOM, the Afrikaans version of the acronym.

- To satisfy the class sensibilities of the white population, Onverwacht, according to one former official, ‘… provided 33 different types of sports facilities including golf facilities, horse riding, an airport, parachuting, rugby, [and] [This] is where all the big bosses of Exxaro [the then ISCOR] and ESCOM stayed, the mine managers, the power station managers, the resident engineers all moved to the area. The upper-class area of Ellisras was around the golf course’ (interview, de Ridder 2015).

- The Conservative Party broke away from the NP in 1982 in opposition to the latter’s apparent compromise on racial segregations and its concessions to big capital (Ballim 2017:85)

- Breaking New Ground is a settlement plan that seeks to ‘promote the achievement of a non-racial, integrated society through the development of sustainable human settlements and quality housing’ (Department of Housing 2004:9).

- The municipality’s Council is made of 26 councillors: 17 of whom belong to the party in power, African National Congress (ANC); followed by opposition parties, Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) at 5, and the Democratic Alliance (DA) at 4 (Lephalale Municipality 2018).

- The Mayoral Planning Committee comprised elected councillors with specific portfolios (interview, Mutshavi 2015), administrative staff from the Planning and Buildings Control departments and was chaired by the municipal manager (interview, Mabale 2015).

- A spatial planning approach which, according the municipality, seeks to ‘optimise the use of infrastructure, increase urban densities; [and] promote integration and compacted settlements (Lephalale Local Municipality 2019: 57).

- See the Lephalale Local Municipality quarterly feedback report to council from LDF for the quarter Oct 2014 to Dec 2014, Agenda for municipal executive committee held on May 29, 2015, item A57/2015[5].

- The interviewee does not say which years but from the time of the interview (2015), this would place it potentially from 2012 or 2013 to 2015.

- MAC Group is a management consulting company that was appointed by Exxaro to manage its projects within the municipality.

References

Agnew, JA (2013) ‘Territory, politics, governance’, Territory, Politics, Governance 1(1).

Alberts, BC (1982) ‘The planning and establishment of the Grootegeluk mine’, Journal of South African Institute of Mining & Metallurgy 82(12).

Ballim, F (2017) ‘The evolution of large technical systems in the Waterberg coalfield of South Africa: from apartheid to democracy’. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of the Witwatersrand.

Bebbington A, L Hinojosa, DH Bebbington, ML Burneo and X Warnaars (2008) ‘Connection and ambiguity: mining and the possibilities of development’, Development and Change 39(6).

Bond, P (2008) ‘Townships’, International Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Buermann, EFW (1982) ‘The establishment of infrastructure for the Grootegeluk Coal Mine’, Journal of South African Institute of Mining & Metallurgy 82(12).

Butcher, S (2018) ‘Making and governing unstable territory: corporate, state and public encounters in Johannesburg’s mining land, 1903-2013’, The Journal of Development Studies 54(12).

Carruthers, EJ (1981) ‘The growth of local self-government in the peri-urban areas north of Johannesburg, 1939 to 1969’, CONTREE 10(7).

Clark, NL (2014) ‘Structured inequality: historical realities of the post-apartheid economy’, Ufahamu: a journal of African studies 38(1).

Department of Housing (2004) Breaking New Ground: a comprehensive plan for the development of sustainable human settlements. Pretoria: Department of Housing.

Fig, D (2010) ‘Darkness and light: assessing the South African energy crisis’, in Bill Freund and Harald Witt (eds) Development Dilemmas in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Gaventa, J (2006) ‘Finding the spaces for change: a power analysis’, IDS Bulletin 37(6).

Greenberg, S (2006) ‘The state, privatisation and the public sector in South Africa’. Southern African Peoples’ Solidarity Network (SAPSN) and Alternative Information and Development Centre (AIDC): Harare and Cape Town.

Hallowes, D and V Munnik (2018) ‘Boom and bust in the Waterberg: a history of coal mega projects’. groundWork Report: Pietermaritzburg.

Houghton, J (2011) ‘Negotiating the global and the local: evaluating development through public-private partnerships in Durban, South Africa’, Urban Forum 22.

Hui, R and JL Wescoat (2019) ‘Visualizing peri-urban and urban water conditions in Pune district, Maharashtra, India’, Geoforum 102.

Institute for Performance Management (2013) Lephalale Service Delivery and Budget Implementation Plan 2013-2014. Lephalale: Lephalale Local Municipality.

Keating, A (2014) ‘Territorial imaginations, forms of federalism and power’, Territory, Politics, Governance 2(1).

Kepe, T and R Hall (2018) ‘Land redistribution in South Africa: towards decolonization or recolonization?’, Politikon 45(1).

Kirshner, J and M Power (2015) ‘Mining and extractive urbanism: post-development in a Mozambican boomtown’, Geoforum 61.

Lephalale Local Municipality (2018) Annual Report 2017-18. Lephalale: Lephalale Local Municipality.

Lephalale Local Municipality (2019) Lephalale Integrated Development Plan 2018/19. Lephalale: Lephalale Local Municipality.

Limpopo Provincial Government (2010) Limpopo Employment, Growth and Development Plan 2009-2014. Polokwane: Limpopo Provincial Government.

Mabin, A (1993) ‘Capital, coal and conflict: the genesis and planning of a company town at Indwe’, CONTREE 34.

Miraftab, F (2004) ‘Public-private partnerships: the Trojan horse of neoliberal development?’, Journal of Planning Education and Research 24(1).

Mocwagae, K and J Cloete (2019) ‘Lephalale: the energy hub of the Limpopo’, in L Marais and V Nel (eds) Space and Planning in Secondary Cities: reflections from South Africa. Bloemfontein: Sun Press.

National Planning Commission (2011) National Development Plan 2030: Our future-make it work. Pretoria: National Planning Comission.

Paton, C (2019) ‘Design flaws hobble Eskom’s Medupi and Kusile power stations’, Business Live, February 12. Available at https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/ companies/energy/2019-02-12-design-flaws-hobble-eskoms-medupi-and-kusile- power-stations/ (accessed January 23, 2019)

Phadi, M and J Pearson, J (2018) ‘We are building a city: governance and the struggle for self-sufficiency in Lephalale Local Municipality’. Research Report. Johannesburg: Public Affairs Research Institute.

Rafey, W and BK Sovacool (2011) ‘Competing discourses of energy development: the implications of the Medupi coal-fired power plant in South Africa, Global Environmental Change 21.

Republic of South Africa (2013) Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16.

Roberts, S and Z Rustomjee Z (2009) ‘Industrial policy under democracy: apartheid’s grown-up infant industries? Iscor and Sasol’, Transformation 71.

Sinwell, L (2010) ‘The Alexandra Development Forum (ADF): the tyranny of invited participatory spaces?’, Transformation 74.

Sovacool, BK and W Rafey (2010) ‘Snakes in the grass: the energy security implications of Medupi, The Electricity Journal 24(1).

Statistics South Africa (2016) ‘Provincial profile: Limpopo, Community Survey 2016’. Report number 03-01-15. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

Tempelhoff, J (2017) ‘The Water Act, No. 54 of 1956 and the first phase of apartheid in South Africa (1848-1960)’, Water History 9.

van Tilburg, L (2020) ‘How to achieve “quick wins” at an “already failed” Eskom – Chris Yelland’, BizNews, January 13. Available at https://www.biznews.com/ thought-leaders/2020/01/13/quick-wins-failed-eskom-chris-yelland (accessed January 31, 2020).

Veti, M (2014) ‘Community development and mining’. Presentation at the Mining Lekgotla: A Purposeful Mining Compass. Available at: http://mininglekgotla.co.za/ 2014/2014-presentations/ (accessed February 23, 2020).

Yelland, C (2019) ‘Load shedding: how series of failures, design flaws brought Medupi to its knees’, Fn24, EE Publishers, October 22. Available at: https:// m.fin24.com/Economy/load-shedding-how-series-of-failures-design-flaws- brought-medupi-to-its-knees-20191022 (accessed January 23, 2020).

Interviews

Cilliers, Valerie (2015) Manager: Communications Division: October 6.

de Ridder, Dries (2015) Former Manager: Town Planning Division: September 17.

Loots, Tienie (2016) Resident and Businessman in Ellisras.

Mabale, Thabiso (2015) Manager: Buildings Control Division: October 8. Martins, Nakkie (2016) Manager: Administration and Support: September 18.

Motebele, Kgoroshi (2015) Former Executive Manager: Strategic Management: September 16.

Mutshavi, Catchlife (2015) Manager: Land Use and Spatial Planning Division: October 5.

Ngobeli, Rudzani (2015) Manager: Public Works Division: August 31.

Radikwabe, Charity (2015) Manager: Local Economic Development (LED) Division: September 22.

Steyn, Ferdi (2015) Phamarcist: Koedoe Apteek Ellisras: October 6. Tukakgomo, Edith (2015) Former Municipal Manager: October 13.

Wepener, Johan (2015) General Manager: Grootegeluk Mine, Lephalale: October 6.