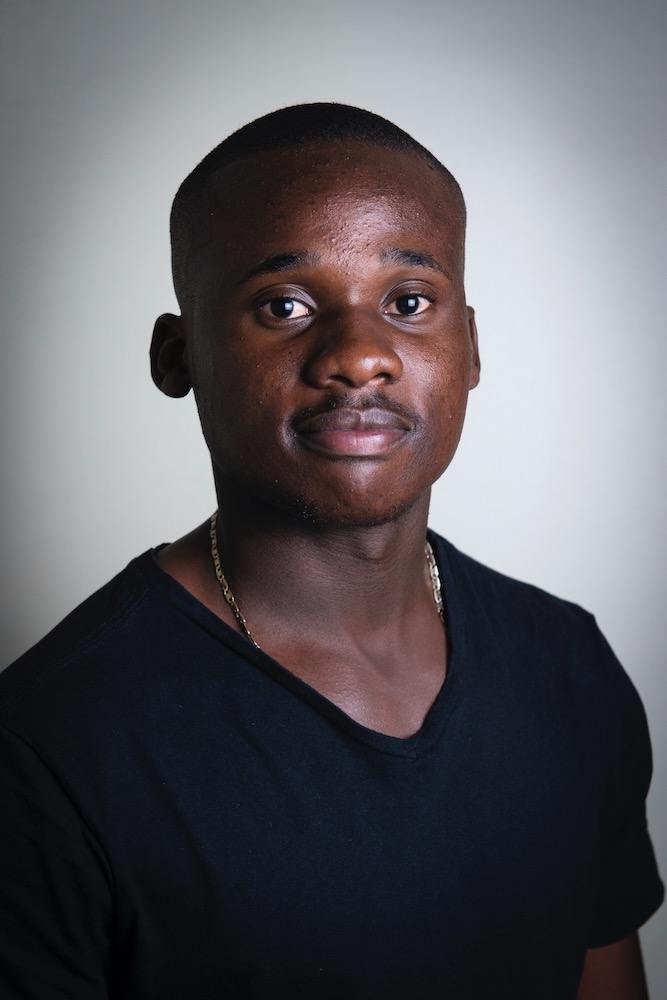

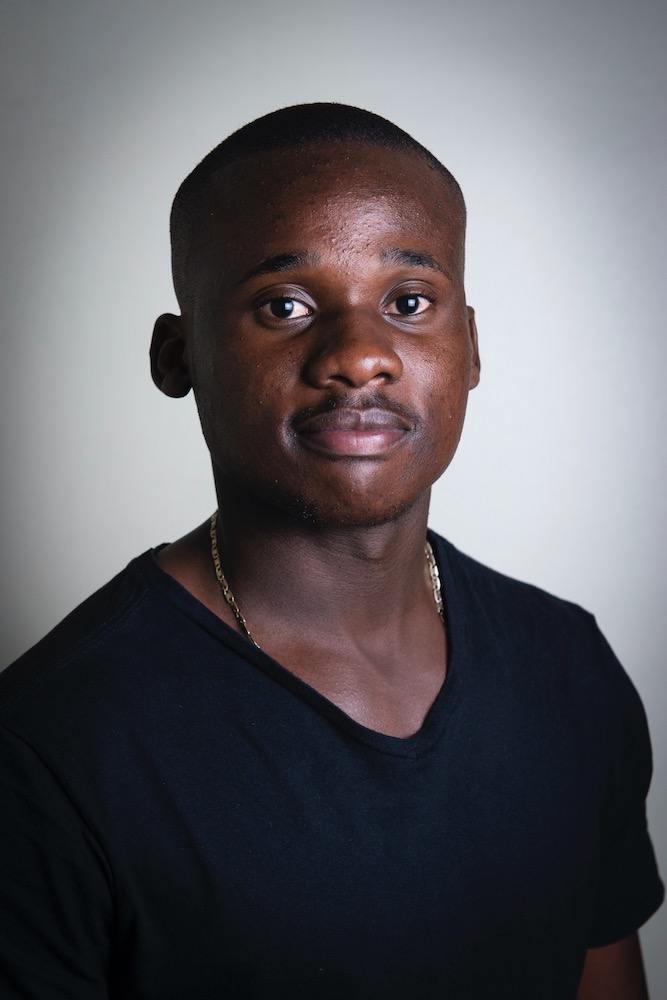

PARI’s intern, Jabu Hlatshwayo, appeals to the President to prioritise land reform and the youth.

Open letter to the President from a Disillusioned Youth

Dear President Ramaphosa

Greetings, Mr. President. I am a 23-year-old University graduate writing to you from Katlehong South in the Ekurhuleni Municipality. I’d like to share my reflections on your sixth State of the Nation Address, which you gave on February 9, 2023.

Even though I applaud and appreciate your efforts in addressing the nation’s current energy crisis, even going so far as to declare a national disaster in response to load shedding, I was disappointed by your failure to address the land reform crisis in your state of the nation address.

In contrast to your earlier state of the nation talks since your inauguration as president of the nation, which emphasised the continued prioritization of land reform as a means of attaining the country’s long-term goals promised in, among other things, the freedom charter and the Bill of rights included in the constitution, the most recent state of the nation address concentrated on what is understandably an urgent reaction to an energy crisis that is disruptive the lives of millions of both young and old citizens of the country, did not do justice to South Africans by overlooking how this crisis is further exacerbated by the increasing unemployment among South African youth unemployment rate, which is higher than the national average , as well as the growth of informal settlements in urban and peri-urban areas because of the shortage of land. I believe that failure to address this crisis is contradictory to the slogan “leave no one behind,”. I believe that until you resolve the historic land reform promises, people like me and millions of South Africans landless youth, will be increasingly impoverished- a situation whose long-term consequences could be devastating for the country.

I watched eagerly your first state of the nation address in 2018, when you pledged your commitment to land reform, particularly to accelerate land redistribution and the equitable access to land through a variety of mechanisms at your disposal to improve food security and redress, this included the expropriation of land without compensation. At the time, I was 18 years old with a Matric pass in hand and on the verge of becoming one of the first recipients of fully subsidized free higher education in South Africa. Without fully understanding what it meant, I was convinced that somehow all of the promises made to poor South Africans about land during the liberation struggle and enshrined in the Freedom Charter and Bill of Rights would finally be fulfilled. I was convinced that your government’s delivery on these promises would make a huge difference on our access to services, sources of livelihood and identity. We could even create our own employment and alleviate the pressure on the nation. Imagine my disappointment six years later when the stat e of the nation illustrated how land reform is no longer a priority. Where does that leave us the unemployed and landless urban youth?

So, Mr. President, in the spirit of Kendrick Lamar’s line, “I went out running for answers,” I reviewed all of your SONA speeches from the years 2018 through 2023 and discovered that your government has placed a significant emphasis on the distribution and issuing of agricultural land, which is in and of itself not a problem as it is in line with your commitment to realizing the enormous economic potential of the agricultural sector (SONA 2018), which includes providing a variety of support services to small-scale and emerging black farmers However, some, including the high-level advisory panel’s report on land reform (2019) and PLAAS’ Andries Du Toit argue that this misses the nature and location of the actual land hunger in this nation, which is felt and urgently needed in the urban and peri-urban areas where 67% of South Africa’s population resides. Living in South Africa’s urban areas, where 44.2% of the population falls below the Upper Bound Poverty Line (UBPL) (Stats SA, 2017), has negative effects, particularly the growth of informal settlements. Nowhere is this felt more acutely than in my municipality of Ekurhuleni, which is home to nearly 122 such settlements .

I personally have to deal with the reality of living in a community with this vulnerability where my family house could be swallowed up by the ground without warning since Ekurhuleni has a history of mining and 52% of our soil is dolomitic. However, there are places like the Makause informal settlement near Germiston, where at least 10,000 people—among them, my older sister’s family—are crammed onto a parcel of land that is vulnerable to mining-related caving and sinkholes.

Most of my family members have chosen to take a chance on their life in order to acquire access to land near economic prospects in Ekurhuleni’s several informal settlements, including Makause. Families like mine across the country construct homes in unsuitable locations like mine dumps, riverbanks, or slopes out of a similar need for land. Recent climatic conditions, like the recent floods, have shown us that this practice is risky and unsustainable, and that the only way to mitigate it is for the government to provide suitable land.

Mr. President, access to land matters just to have a place you can call your own, where you do not have to pay exorbitant rent or worry about being evicted or living in a falling house, where you struggle to complete a simple task like buying a sim card in retail outlets because you lack proof of residence, but most importantly, it provides a basis for the youth to secure employment or create their own. But Mr. President, in order to achieve the constitutional imperatives outlined in Section 26 (which deals with the state’s obligation to provide access to adequate housing), as well as the principles of the Freedom Charter (which asserts that unused housing space shall be made available to the people), you must act urgently to facilitate the release of land for agricultural and settlement purposes, particularly in peri-urban and urban areas.

The High-Level Advisory Panel on Land Reform’s (2019) report urges a change in land reform policy priorities to include an urban land policy that focuses on both fair access and tenure type. They point out that Section 25 (5–6) of the Constitution, which mandates tenure reform and redistribution, applies to urban areas and should be interpreted along with Section 26. (Which deals with housing). The panel (2019) also recommends several significant measures to release land for housing and supports the use of the Constitution’s expropriation without compensation powers. Disappointingly, the last recommendation, which called for legislation to be introduced to amend section 25 of the Constitution (the Expropriation Bill), which would have made expropriation of land without compensation part of the Constitution, has not yet been signed into law. Although the measure was defeated in 2021, I still want to thank you for your work and dedication to speeding land redistribution and land reform.

However, I believe that the Expropriation Bill, when read in conjunction with the Panel’s proposed Urban Land policy provide a framework to guide the redistribution of land and ensure that all people have equitable access to it. The Expropriation Bill, which will allow for the expropriation of land without compensation in certain circumstances, such as when it is state land, abandoned land, or kept for speculative reasons, can assist alleviate the urban land shortage in Ekurhuleni. The municipality of Ekurhuleni has idle land, including abandoned factories and warehouses, which it cannot access because the land belongs to private landowners. The municipality has trouble accessing and using government land because of the drawn-out procedures required to take possession of the property.

More concerning is the municipality’s failure to access its own land that is tied up in 99 years leases to private institutions and individuals. During the transition period, these leases were signed at a nominal rate. Even though this issue has been raised in various forums – I find no urgency on the part of the government to resolve this issue.

Mr. President, the approval of the urban land reform policy and the Expropriation Bill will allow for the acceleration of land reform in order to address the vulnerability of the urban poor and youth (who make up the majority of South Africans), as well as achieving the nation’s long-term goals outlined in, among other documents, the freedom charter, the Bill of rights enshrined in the constitution, and other international calls to end inequality like the United Nations’ SDGs.

For me, it would mean addressing the urgent need for land in my own municipality, including the needs of those whose homes are being swallowed up by sinkholes and those, like my older sister living in Makause, who are constantly vulnerable. By ensuring equal access to land, especially in peri-urban and urban areas, you would be empowering the majority of South Africans to participate in ownership, food security, agricultural, and other land reform initiatives.

But ultimately, this all points to the need for the state giving urban land reform priority. I therefore plead with the president to sign the bill into law (and establish an urban land policy) within the bounds of your constitutional powers, not to benefit a few but especially the youth of South Africa who constitute a significant majority of the population.

Jabu Hlatshwayo, Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI)