by Thina Nzo

It’s been five years since the last local government elections were held in 2016. For South Africans, that means its time to go back to the voting booth after the Constitutional Court ruled that local government elections must be held no later than 1 November 2021.

With the elections drawing closer, there are the usual numerous controversial misgivings from political parties and mounting discontent from citizens. This year certainly proves to be no exception.

The local government elections stage has been set with an added plot twist of a recent insurrection and looting that took place in Kwazulu-Natal and parts of Gauteng during a worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, exposing our city governments’ shortcomings in resolving the glaring socioeconomic inequalities in urban communities.

There were concerns about Covid-19 health risks associated with holding elections, resulting in questioning the Electoral Commission of South Africa’s (IEC) state of readiness to hold a free and fair election under these circumstances.

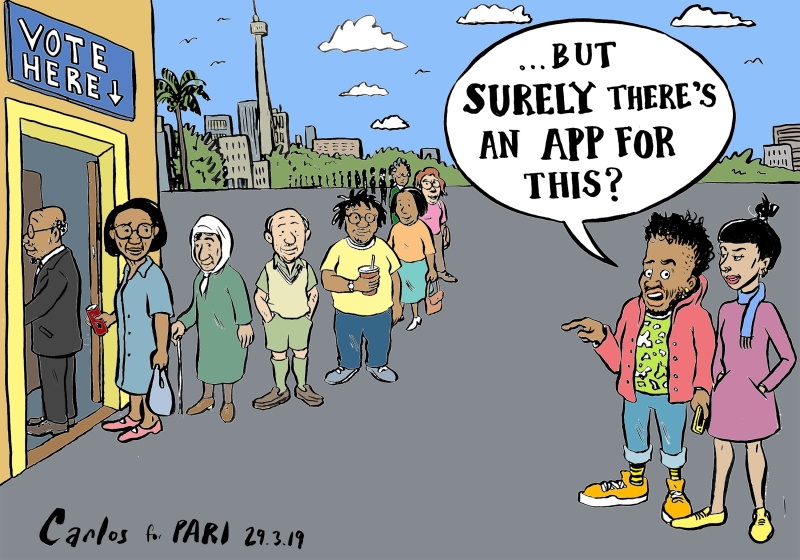

Nevertheless, it became obvious that political parties’ main concern was their inability to hold mass campaigns ahead of the polls in a precarious sociopolitical environment. While the IEC has fallen short of taking up modernised digital solutions such as electronic and email voting that would have ushered in an era of e-democracy, we need to bear in mind that the IEC is dependent on the ICT infrastructure as an enabler.

South Africa’s staggering digital divide and inequality, slow digital migration and sluggish technology systems have been stumbling blocks for digital voting migration. Under the current pressures, the IEC has published a feasible election timetable accompanied by reopening the voters’ rolls and candidate nomination process. The latter is currently being challenged by the Democratic Alliance (DA) in the Constitutional Court.

The enormous task that lies ahead for the IEC is ensuring that approximately 75 million ballots are printed before 1 November and putting up rigorous Covid-19 mitigation measures.

Therefore, the likelihood of having elections during politically tense and precarious times has been the main source of anxiety of unpredictability for political parties,who have made little effort in the past five years to ensure that city governments are run in a manner that is transparent, accountable and efficient; in distributing resources to address service delivery backlogs, poverty, unemployment, inequality and development.

The slow vaccine rollout and uptake, coupled with a disillusioned citizenry, raises the probability of seeing a decline in voter turnout, which may plunge city and local governments further into hung councils and instability.

Low turnout

As we have seen on the voter turnout map and trends in Gauteng in the previous local government elections, the ANC has been clamouring to reclaim its power since it lost majority seats in the City of Johannesburg (CoJ) council as the result of a dramatic decline in voter turnout in ANC strongholds, compared to areas where the DA had a support population.

These areas were mainly Soweto and the northen suburbs of Johannesburg, where voter turnout was less than 40%; and the ANC only got an average of 57% and the DA 15%.

Meanwhile, in areas where the DA had a substantial support population, the turnout was 70%, managing to scoop an average of 69% votes, leaving the ANC with 20%. We are also seeing a gradual constituent rise in the overall IEC candidate nomination list, which increased from 855 in 2016 to 944 in this year’s elections.

Despite this, the doleful low voter turnout in municipal elections is not just a South African phenomenon. Western democracies such as England have been struggling with poor voter turnout since 2010.

The recent 2019 local government elections held in England recorded a voter turnout of 12.7%, while South Africa had an overall 58% in the previous 2016 election. Apathy, delusion and stagnant change have been common denominators for citizens, particularly those who disengage from local government by staying away from the polls.

The corroboration between voter turnout and declining voter confidence in traditional strongholds of political parties helps us to predict the voter outcomes.

Recent Ipsos polls placed the ANC at the forefront with a 40% voter support. This may be influenced by the currently precarious sociopolitical environment, mired in the DA’s intrapolitical battles, the controversies surrounding ‘kingmaker’ smaller parties such as the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) and the Patriotic Alliance (PA) that have contributed to the instability of coalitions in the city council, which places the sustained predictability of hung councils alongside unpredictability and speculation in voter share.

Missing the boat

While clinging to traditional rallies and door-to-door as political campaign vehicles, parties have missed the boat of tapping into alternative campaign platforms in the time since the preliminary election date of 27 October was announced by President Cyril Ramaphosa on April 21st, 2021. On the other hand, political parties are still able to engage in robust debates and engagements with their constituencies by seizing the opportunity to relaunch voter education through deliberative democracy using available technologies that can facilitate participation.

Ward candidates still have a window to re-engage the electorate on social media platforms where urban youth is predominantly found, using the current public discourses of rebuilding communities, obtaining feedback and ideas on how to reform local government’s poor state of political governance and leadership, accountability, transformative socioeconomic development and the delivery of services.

The dependency on traditional platforms, which are costly and less engaging, can stifle political parties’ transcendence towards e-democracy and e-participation. With little time before the elections, the question is: are parties ready to test their political clout and confidence by moving out of their political comfort zones and into unchartered digital spaces to ensure a free and fair election is achieved through robust deliberative engagement with citizens and the youth.

As the date creeps closer, the country waits with baited breath to see what is set to be an intriguing and unpredictable local election.

It is open season and it could be anyone’s game. But we can be certain that, after the debacles we have witnessed since Covid landed on our shores, citizens are ready to administer some cold realities and exercise their democratic right to demand accountability.