By Dr Mbongiseni Buthelezi

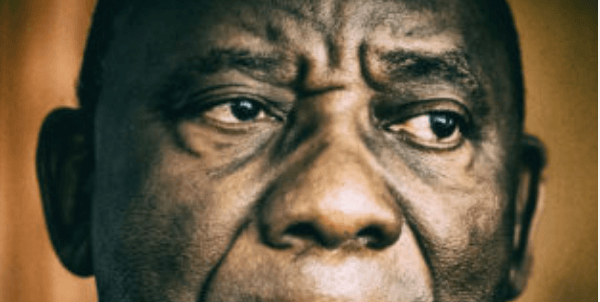

In the 2020 State of the Nation Address, President Cyril Ramaphosa presented an impressive gamut of key initiatives that need to be or are already being done by the state and the government. They are forward-looking, aspirational and practical. I listened closely to a SONA for the first time in many years.

Sincerely, even desperately, I wanted to believe him – that the nine TVET colleges will be built and be of good quality; that 1,000 young entrepreneurs will be successfully supported to develop thriving businesses; that the energy crisis will be fixed and that the district development model will yield municipalities that meet the needs of their residents.

Yet, haven’t we been here before – every year, in fact? Another year, another SONA and we wake up the next day to a country in continuing decline?

At least we’ve come a long way from ex-President Zuma’s yearly yawn fests. Each time he himself sounded unconvinced and surprised by some of what he mouthed.

But there was more conviction from Ramaphosa, and willingness to face up to and name the fact that we are in a crisis. The speech centred on what needs to be done, rather than basking in the diminishing glory of what has been achieved since 1994. However, all around scepticism lingers – on social media, talk radio and in office corridors.

This SONA, Ramaphosa himself and the government as a whole have quickly run up against a trust deficit in society. Hardly anybody really believes that we are going to see meaningful implementation of the turnaround of Eskom or SAA, or that water-use licences are going to be issued within 90 days.

Ramaphosa seemed painfully aware of this. He repeatedly made a call for creating social compacts to achieve the growth of the country’s economy, saying that we need to work together to create jobs, improve education and fight corruption.

“Our history and contemporary experience has taught us that if we are to achieve what we set out to do, we must focus on what unites us, instead of divides,” he said.

The president presented credible plans for different sectors. They are focused and pragmatic. Why, then, the tangible lack of trust that they are going to be implemented?

The answer lies in state institutions and their capability. The first capability issue is historical. Apart from a few pockets of the state such as SARS, since the advent of democracy, governments have hardly paid serious attention to how to build the administrative capabilities in each national and provincial department and in every municipality to deliver on their promises.

The approach to how we staff the Home Affairs department or the supply chain management function of any municipality is at best haphazard. The result is that the services we receive are a lottery – good in one place, indifferent in another and often downright hopeless.

The second problem is that this decline of administration and governance at every level makes it a daunting task to turn the ship around. Political interference in appointments of officials down to the lowest levels in some municipalities, provincial and national departments, has had a severely demoralising effect on some public servants.

The problem was brilliantly illustrated by one image after the SONA speech, where Minister of Justice Ronald Lamola was speaking about what they are doing to fix the National Prosecuting Authority, which was gutted under the Zuma administration. Directly behind him was Duduzane Zuma posing for pictures.

What does it communicate to a state official at the lowest rank of the public service to see people like Zuma, who are alleged to have had a strong hand in State Capture, living it up? What does it say to all of us to see on the benches of Parliament men and women whose names are tracked all over the Zondo commission, continuing to be our public representatives? How do we trust that something different is going to happen this time?

[…]